Why interruptions are frustrating to developers

- Artículo extraído desde: https://tellspin.app/blog/why-interruptions-are-frustrating-to-developers

Imagine your focus was a card tower and interruptions were knocking it down. If your productivity depended on having a card tower, wouldn’t you get frustrated?

I heard this analogy from a friend of mine several years ago. I’ve repeated the analogy for a quick visual of focus and have always liked it, so I reached out to my friend to see if he had a source.

If you’ve ever attempted to build a card tower, you know how time consuming it can be to balance the cards and control the environment around you. It’s especially frustrating when your friend closes a door and causes a rush of wind that somehow finds a direct path towards your card tower.

Just like card towers, a developer’s focus is carefully built, combines multiple items together, and can be easily destroyed.

Focus fuels flow

Coding requires a great deal of thinking. Some days are better than others, but the goal for each day is to achieve flow or a state of absolute focus.

Also known as “the zone,” flow is the mental state of operation in which a programmer is immersed in a feeling of energized focus, complete involvement, and enjoyment in the process of coding. Flow is not a concept unique to computer programming, but software developers are very familiar with it.

- CoderHood 15 Best Ways to Achieve Flow

Once I’m in flow, I want to keep it that way as long as possible. It’s not voodoo magic or anything, but it’s enjoyable to be completely immersed in my work.

Many have different opinions of flow, but a common theme is that it is a period of time where your best work happens. Take a look at some of the top results of a google search for “software achieving flow” and see for yourself. You’ll find: The importance of flow in software development, How To Get Into Flow State | Become A Productive BEAST!, and Flow in Agile Software Development: What, Why and How.

The articles relate how flow is a period of time where you achieve your best work. In my experience, it’s not necessarily when I do my best work; it may be the only work I accomplish in a day.

Building a Tower of Focus

Getting to flow requires focus and is a complicated subject. Factors in flow can range from how much sleep I’ve had, if work is challenging enough or too challenging, my salary, the company’s vision, all the way down to if I like my co-workers or not.

To simplify flow a bit, I’ve decided to narrow it down to the process of gathering context (or information) of a bug in a piece of code. Gathering context is a long and tedious process. To illustrate, I’ve attempted to walk through what goes on during a typical coding session. It starts with building a Tower of Focus.

The tower has a foundation, middle layer, and peak. A simple 3-layer card tower has 15 cards. 8 cards for the base, 5 cards for the middle, and 2 cards for the peak. I’ve named the layers “The WHY”, “Trade-offs”, and “Verify”, respectively.

Each one of these cards is context for the task I’m doing. I build these layers one card at a time, carefully leaning them against one another.

Base - Understanding the why of the code

The base layer represents finding “the why”, or the original intent. It is the hardest context to gather, in my opinion. In order to make a change to code with confidence, I need to discover the initial intent that went into it.

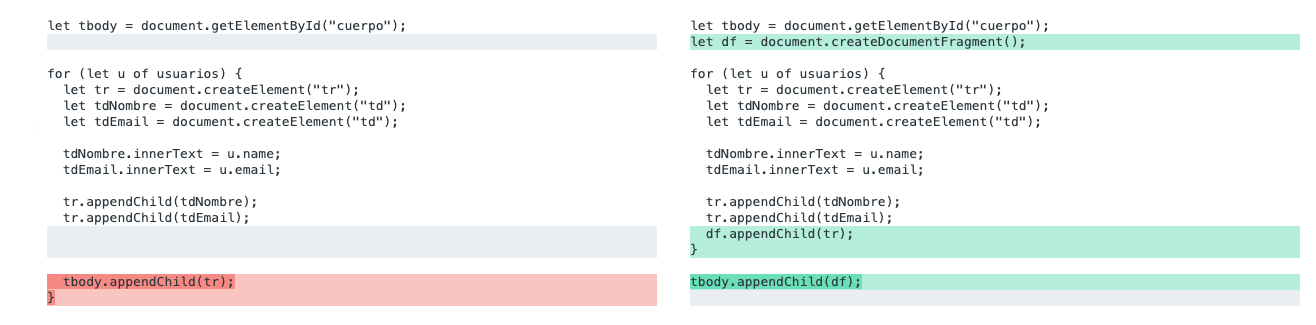

So what does looking for intent look like? Let’s look at a piece of code.

It’s pretty obvious there were some things the original author discovered when writing this. I can tell because they’ve put lots of lines with comments (lines beginning with //). I’ll start to wonder, why did they put so much effort into this?

The surprise comes when learning that this code is part of a bigger

picture and any change to it can have unintended side-effects higher up

in the chain. (It’s executed from a spaghetti of methods and is inside

multiple for loops).

If I’m investigating a bug related to this code, I’ll have to digest

each one of the lines. Variable names such as reader and n, the

subtle differences between each if statement, etc. As I go, I add a

card to my focus tower for each one.

I’ll explore tests, commit messages or even chat with the original author (if they’re still around) to try to understand what they were trying to do. Finding original intent is more or less like being a detective in a murder mystery.

Except the above is the exception to the rule. It actually had comments…

What usually happens is I’m thrown into the same kind of code as above,

but with no comments and useless commit messages. I really have no other

choice but to read all of the code to understand it in it’s triple

nested for loop glory.

To make matters worse, it’s only lightly tested which puts me at a crossroad. If I change it, I’ll have no idea if I’m setting a land mine to be later detonated at the worst possible time.

Do I spend a large amount of time improving the tests or do I just cross my fingers, test it a little bit and move on?

Each thing I discover keeps adding cards to my base layer of my focus tower. If the code is even slightly complicated, I’m setting myself up to build a 4-layer or even a 5-layer focus tower. In this case, let’s say I only needed a 3 triangle base or 3-layers overall.

Middle Layer - Trade-offs and workarounds

The next layer is determining what needs to change or what is broken and how it can be fixed.

Continuing with the example of fixing a bug, I’ll start diving into where certain log messages were printed in which parts of the code. A log message can be thought of as evidence or a record of a program’s behavior (the blood on the carpet, if you’re a detective). Sometimes logs show a complete picture, but often they’re incomplete and missing information.

What I’ll have to do is try and reproduce the bug. I’ll add more log messages or I’ll use a debugger tool (a way to walk through a program one line at a time). I’ll add some comments or notes about how it executes. I may change a variable or two to see how it impacts the output of the program. Usually by doing these things a few times I can narrow down or isolate what section of the code is broken.

If I’m lucky, I get a solid reproduction of the bug and that’s enough to figure out a fix, but otherwise, I need to list out a couple trade-offs or workarounds. The harder problems can be solved in varying degrees but it essentially boils down to 2 options:

- A real fix (takes a lot of time)

- A hotfix (may break later, but is really fast)

More often than not, the business is okay with the hotfix to get the problem solved faster (that’s a subject for an entire blog post for another time). All of it adds cards to my tower and it becomes quite the balancing act.

Peak - Test and Verify

The final layer is making sure it works in production. Production is just a fancy word for the customer-facing part of software. Best practice is to add some tests, but sometimes a dry run of the code on a developer’s computer will do. The important part is to continue on while the context is still fresh in your head and the layers are still stacked on one another. At that point in time, you know the most about the code and how to fix it if something goes wrong.

Interrupted flow - Perils of context decay

In the perfect world, I would be free to move from the base layer, middle layer, and then onto the peak with no interruptions. But the reality is, my day is broken up with meetings or interruptions.

Charity Majors, the CTO of Honeycomb, says it best when referring to why they practice “15 minutes or bust”.

If you have a rapid feedback loop…You have that original intent that’s fresh in your head, you know exactly what you’re trying to do: the why, all the trade-offs you had to make, all the variable names, and everything. You can never get that back again. It starts to decay immediately as soon as you switch your focus away from it…

- Charity Majors, CTO of Honeycomb, The New Faces of Continuous Improvement

Imagine I’ve just spent a couple hours building my focus tower and then the rush of wind hits. An interruption. I get paged to help solve problem X and it’s super “urgent” (In Slack, @channel is a way to notify everyone and implies urgency).

@channel just wanted to let you know that we changed the meeting in two weeks to Friday. The update is in your calendar

@channel so and so just wrote in saying they’d like to try X. Is that possible?

Since they’ve used the signal that an enemy has arrived and war is about to break out or otherwise known as @channel, I feel like I’m immediately obligated to help.

I’d say 95% of the time @channel is unnecessary and is a great contributor to destroyed focus towers. Most things can wait for support meetings or handed off to a single person assigned to help that day. Shifts can be scheduled on a rotation to spread the task across multiple team members (checkout Tellspin as an easy way to rotate @mentions in Slack).

These interruptions pull me from my work and my focus tower immediately starts to decay. If I’m away for an hour or more, you might as well just point a hair dryer at my tower and blow it over.

To be clear, small interruptions for a few minutes are usually okay. I can return back to my task without noticing. I’d argue, however, even from a small nudge, there’s a high risk that I won’t bounce right back to what I was doing. I’ll go off and check my email or view the likes on my twitter feed. The longer it takes to get back to my original task, the greater the extent of the decay.

Battling context decay

So what can we do? The most important thing is to be aware that interruptions aren’t free. There’s probably a reason that your co-worker put a block in their calendar or has periods of do not disturb set. Be nice to one another.

On the other hand, I’m often my own worst enemy when it comes to distractions. I’ve compiled a list of things I’ve found helpful for me to focus.

1. Reduce Slack interruptions at a team level

If you specifically deal with interruptions from Slack, take a look at my tips for reducing Slack interruptions for your team. It talks specifically about ways you can work with your frontline support teams to help spread the interruption load across your internal team members. My recommended tip from there would be to plan for interruptions by setting up a on-call rotation shift schedule.

2. Create friction to your distractions

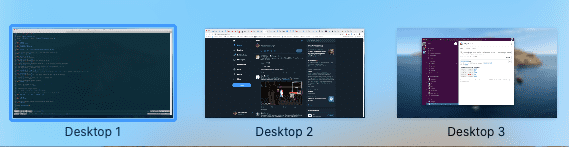

I created a tiny bit of friction by moving my top distractions to another desktop such as Slack, twitter, linked-in, or email to a different desktop. Whenever I get the urge to look at those things, I have to press a few keys to switch. The friction serves as a reminder that I wanted to focus and works great. I’ve also increased friction further by minimizing the window or closing it altogether.

3. Create an off-limits chrome tab group

One thing I struggle with is checking the metrics of my business constantly. To assist myself in this goal, I created an off-limits red chrome tab group.

The group contains communities I belong to, linked-in, twitter, Slack, and my analytics pages. I know to not open the group during periods of deep focus. Yes, yes, I know, I could close the tabs altogether, but I have a habit of reopening sites. Keeping them locked up in a group helps me remember they’re my top distractions.

Another thing I’ve been trying to adopt is strategy laid out by Michael Lynch of only checking metrics once a week on the end-of-day Friday. He also had trouble with metric checking:

Checking metrics is “shallow work”: it doesn’t require deep focus or critical thinking, but it feels productive. … Until I broke the habit of constant stat-checking, I never realized how much space it occupied in my brain.

- Michael Lynch, How to Grow Quickly and Never Turn a Profit.

4. Record context as you go

The final tip to combating context decay is making notes as I go. What I

like to do is have a bash script in each directory named .zing. It’s

ignored by my global git-ignore so I can place them right alongside the

code I’m working on. Here’s an example of one I was working with last

week.

#!/bin/bash

# Todos:

# - check if ran twice if it updates the usage for that day

# - use end_ts for date

# - use the last-in record

# - ceil monthly usage 219.002 == 220

./report_to_stripe.rb 05/

exit

../bin/monthly_report.rb 05/

exit

My .zing file serves two purposes. It keeps a list of todos and notes,

but it also is a history of the last command I executed. When I come

back in the morning, I can execute the script, see the output of the

code, and jump start my day back into what I was doing.

I use https://github.com/jewel/zing to execute the script from vim or

my terminal by typing ,z. It’s a handy way to speed up my iterations

too.

Let’s build focus towers together

Everyday is a battle to keep my focus tower built and free from the rushing wind of distractions and interruptions. Working together to stop unnecessary interruptions is a team effort and if done correctly can have a huge impact on productivity and increase developers chances in reaching flow.