The Productivity Funnel

- Artículo extraído desde: calnewport.com/blog

In light of our recent discussions of “productivity,” both in this newsletter and on my podcast, I thought it might be useful to provide a more formal definition of what exactly I mean when I reference this concept.

In the most general sense, productivity is about navigating from a large constellation of possible things you could be doing to the actual execution of a much smaller number of things each day.

At one extreme, you could implement this navigation haphazardly: executing, in the moment, whatever grabs your attention as interesting or unavoidably urgent. At the other extreme, you might deploy a fully geeked out, productivity pr0n-style optimized collection of tools to precisely prioritize your obligations.

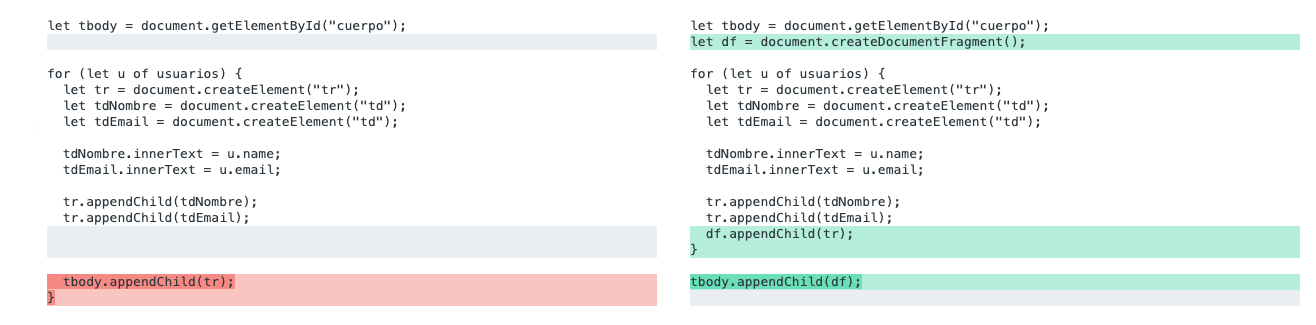

To make sense of these varied journeys from a broad array of potential activity to the narrowed scope of actual execution, I often imagine the three-level funnel diagramed above.

The funnel begins with the fundamental task of selection, where you determine which activities to commit to accomplish. Relevant ideas for this level can be found in books like First Things First, Essentialism, How to Do Nothing, One Thing, The Dip, and Year of Yes.

Once committed, these activities must then go through processing, organization, and storage. There are two goals for this funnel level: to avoid forgetting what you’re supposed to do, and to make smart decisions about what to work on next. Relevant ideas for this level can be found in books like Getting Things Done and The Bullet Journal Method. This is also where the Capture/Configure/Control philosophy I talk about on my podcast, or software like OmniFocus, Trello, Basecamp, and Asana, can help.

The final level focuses on the actual execution of whatever it is you’ve figure out you should be doing in the moment. This includes how you plan your day, the rituals you deploy to support your efforts, and the processes you’ve put in place to support more effective collaboration with others. Relevant ideas for this level can be found in books like Deep Work, A World Without Email, Daily Rituals, The War of Art, and Bird by Bird. Planning tools like my Time Block Planner are also useful here.

There are obvious benefits to defining the concept of productivity with this level of detail.

For one thing, it helps avoid the common mistake of focusing on one part of the funnel while avoiding others. There are many deep work aficionados, for example, who are obsessive about their depth rituals (execution), but are constantly forgetting or losing track of what’s on their plate (organization).

Similarly, it’s common to come across productivity geeks with complex organizational systems, who pay little attention to their overall workload (selection), and end up hopelessly overwhelmed, no matter how much they optimize their OmniFocus configuration.

By clearly delineating the three different levels of the productivity funnel, you can make sure each level gets at least some attention.

This detailed definition also adds nuance to anti-productivity criticism. A lot of this recent debate loosely associates the term “productivity” with an exploitative capitalist drive to maximize accomplishment. When viewed against the specificity of the productivity funnel, however, it becomes clear that this critique more accurately concerns only the activity selection level.

I agree that there’s an important debate to be had about how organizations and individuals implement activity selection (e.g., my recent post on slow productivity), but regardless of where this debate takes us, the other levels of the funnel remain important and largely orthogonal. In a post-capitalist collectivist utopia, where work is optional, and we’ve excised our souls of our past bourgeois internalization of the narratives of production, we’ll still have things we need to get done, and having an organizational system will still be better than haphazardly trying to keep track of these things in our minds (even Lenin had a task list).

Similarly, intentionality about execution can often enhance — not impede — slower lifestyles. If you don’t give serious thought to how you want to structure your days, it’s all too easy to fall back into distraction and shallow busyness.

I’m not sure if the funnel proposed above is complete. Indeed, I’m almost certainly missing aspects of productivity that are equally as important as the three levels I detail. But the more general movement here toward clarity in what we mean when we talk about productivity is worth encouraging.